Writer Profile

Kalki: A writer for all seasons

by Gowri Ramnarayan

Pride in one’s heritage, an attempt to understand the past, and the determination to enable a better future — these are perhaps the most vital sources of energy in Kalki R Krishnamurthy (1899-1954), an iconic novelist and a pioneer of modem Tamil literature and journalism.

A prolific writer, he turned out, besides novels and short stories, political essays, reformist propaganda, travelogues, music and dance critiques, film reviews, biographies, scathing satire, humorous essays, songs, poems, a film script or two, and translations, including Mahatma Gandhi’s The Story of My Experiments with Truth.

Revelling in polemical debates on issues political, aesthetic and ideological, Kalki used his writing talent to crusade for several causes. Liberal humanist as he was, he had chosen his pseudonym ‑- the name of Lord Vishnu’s final avatar for the destruction of the world -‑ because he was singularly resolved to “destroy regressive regimes, express radical thoughts, take readers into new directions, and create a new era”! Quite apart from his political and reformist manifestos, artists remember his contributions to the renaissance of the performing arts in Tamil Nadu. His critical analyses promoted the highest aesthetic values with unflinching honesty.

Today, Kalki is best known for his historical fiction, a genre in which he remains unsurpassed. His Sivakamiyin Sapatham, Partiban Kanavu and the mammoth Ponniyin Selvan recreate the glorious eras of the Pallavas and the Cholas with their magnificent tradition of art and culture, which are brought to bear on contemporary Tamil self-fashioning. Alai Osai, which the author deemed his best work, documents the turbulent decades of the freedom struggle between 1934 and 1948, seen through the eyes of ordinary people who are inevitably affected by the sociopolitical changes.

Born in a poor brahmin family in Puttamangalam village, Thanjavur, in the Madras Presidency, Krishnamurthy’s education began in the classes conducted on the front verandah by the teacher who lived next door, continued in a more formal village school and ended in Tiruchirapalli town. A brilliant academic career was cut short when he left school to answer Gandhi’s call for non-co- operation with the foreign regime. This is how he describes how he was arrested for making a seditious speech against the British government at a public meeting on 24 September 1930.

“I was charged with having broken the order as per section 144, thereby disrupting public peace and causing distress to the people.

This was my testimony in court: “It is true that I wilfully broke the order as per section 144. But it is not true that I disrupted public peace. That would be against my dharma. It is also false to claim that I caused distress to the people. On the contrary, as they listened to my speech, members of the audience frequently burst into loud, gleeful laughter. The head constable who testified against me just now as a witness, also joined in that laughter.”

This last sentence caused a ripple of laughter in the courtroom. The magistrate was not amused as he passed the sentence – “Six months’ imprisonment.”

Young Krishnamurthy’s induction into journalism was facilitated by his involvement with the freedom struggle. His career began in the patriotic journal Navasakti and in the Congress leader C Rajagopalachari’s anti-liquor magazine Vimochanam. Very early did Rajaji become his political guru. All his life, Kalki remained his faithful lieutenant, despite the fact that this allegiance prevented the writer from winning acceptance from opposing camps for his creative achievements.

It was when he joined SS Vasan’s Ananda Vikatan that Kalki became a household name, even as he made that magazine hugely successful. Here he began what was to be a lifelong practice – which was the promotion of many writers of talent, women among them. In 1941, Kalki founded a magazine in his own name, with the help and co-operation of his friend T Sadasivam, and with funds raised by Sadasivam’s celebrated Carnatic vocalist wife Subbulakshmi.

Though he did wield considerable influence as an opinion maker, it was through his fiction that Kalki captured the hearts of Tamils who eagerly awaited the latest instalments. Old timers recall reading the copies as soon as they bought them, even as they walked on the street on their way home, before they could be grabbed by equally eager family members. Many others will recall that listening to a family elder read aloud Kalki’s novels was an abiding memory of their youth. His effortless fluency, sense of humour and felicitous use of language combined to communicate his ideas in a striking and original manner. Critics have come up with a name for his original style: Kalki-tamizh. All this led to a fellow scribe describing him as a film star among writers, not in unmixed praise, and certainly with some envy.

Kalki was not content to remain behind the desk. He was an adroit and sought-after speaker on many subjects. He was adept at raising funds and mobilizing resources for many causes. He masterminded the construction of a monument to the poet Subramania Bharati in his birthplace Ettayapuram, and the Gandhi Mandapam in Guindy, Chennai.

Fellow-writers were always sure of help when they needed it. When noted Tamil writer Pudumaipitthan passed away, it was Kalki who raised funds to provide financial stability to his wife and child. And this despite the fact that Pudumaipiitan had ceaselessly attacked Kalki, sometimes below the belt. Similarly, his unrestrained praise of the powerful writings and oratory of CN Annadurai and M Karunanidhi of the Dravida party, whose principles he strongly refuted, demonstrate that he did not mix politics with aesthetic appreciation.

Fellow-writers were always sure of help when they needed it. When noted Tamil writer Pudumaipitthan passed away, it was Kalki who raised funds to provide financial stability to his wife and child. And this despite the fact that Pudumaipiitan had ceaselessly attacked Kalki, sometimes below the belt. Similarly, his unrestrained praise of the powerful writings and oratory of CN Annadurai and M Karunanidhi of the Dravida party, whose principles he strongly refuted, demonstrate that he did not mix politics with aesthetic appreciation.

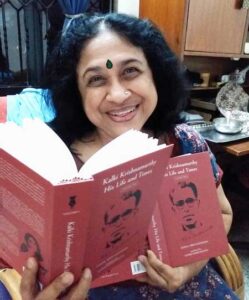

Translating Kalki’s monumental biography by ‘Sunda’ MRM Sundaram taught me something about Kalki’s values. Kalki saw his writing as a mission for him to promote the values he considered indispensable for making life meaningful. And to him the act of writing itself was an expression of human rights and human freedom. More, it was also the means of using his freedom to fulfil his responsibilities as a son of the Tamil realm, as an Indian, and as a citizen of the world.

Gowri Ramnarayan is a journalist, author, playwright and award-winning theatre director. She is the founder of JustUs Reportory, whose plays have been staged in India and abroad. She has translated into English a comprehensive biography of Kalki in Tamil, an excerpt from which begins on the next page.

Book Excerpt

When Rajaji refused to raise Kalki’s salary!

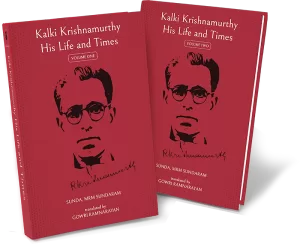

This excerpt from Chapter 16 of Kalki Krishnamurthy: His Life and Times, translated by Gowri Ramnarayan from ‘Sunda’ MRM Sundaram’s biography of the writer, details young Krishnamurthy’s encounter with the statesman who would become an august national leader, also his cherished role model.

At this time, the young man had just finished his first term in prison as a freedom fighter and was working for the Indian National Congress.

Most of the chapter is in Kalki’s own words.

“After spending all of 1922 in prison, I was released in early 1923. I was preyed by anxiety. “What am I to do now?” S Ramanathan, who was then secretary of the Tamil Nadu Congress Committee, put an end to my anxiety. His committee’s headquarters were in Tiruchirapalli. And there he gave me the post of a clerk, with a salary of Rs 30.

My family and friends were happy to know that the Congress paid any salary at all. But I was not happy. Do you know why? There was another clerk in the same office. He and I had been classmates. He did not quit school to join the non-cooperation movement as I had done. He was no great shakes in studies. He had not served the Congress for free, nor had he gone to prison. He got employed in this office when I was in prison, and was now earning Rs 40.

What irked me was this: I who had made sacrifices and undergone imprisonment was paid Rs 30, and he who had done nothing at all got Rs 40. This thought ate into me. Therefore, a few months down the line, I applied for a raise in my salary. S Ramanathan who was very fond of me, added my request to the agenda of the next working committee meeting.

Meanwhile, Rajagopalachari asked Ramanathan to prepare a pamphlet in Tamil. Ramanathan asked me to do it. It was sent to Rajaji for approval.

The moment he got out of the train in Tiruchi, to attend the state executive committee meeting, the first thing Rajaji asked Ramanathan was, “Who wrote the pamphlet you sent me? Ramanathan pointed to me, standing nearby.

“What does he do?”

“He works in the state executive committee office.”

I thought I saw signs of approval on Rajaji’s face. For a few minutes he talked about nothing but the pamphlet, saying how he liked everything about it, including the handwriting.

“Good. The master is happy. He will increase my salary,” I thought.

When this matter came up in the committee, Secretary Ramanathan recommended a raise of Rs 5 in the clerk’s salary. Dr Rajan, who had been responsible for my leaving school and who had a special fondness for me, enthusiastically seconded the proposal. The others agreed. Ramanathan was just about to note it down when Rajaji, who had been lost in thought until then, broke in to ask, “Who gets an increment?” I felt uncomfortable.

Since the others said nothing, Rajaji looked at me and asked, “Why do you want an increment?” I stayed silent. He began to shower me with questions.

“Are you married?”

“No.”

“Your parents?”

“My mother is alive.”

“Does she live with you?’

“No. She lives with my elder brother.”

“Do you have anybody else to support?”

“No.”

“When you live all by yourself, is Rs 30 per month not enough to meet your needs?”

“Enough.”

“Then why do you want more?”

Silence was my answer. I couldn’t have told him what I had in mind, could I? Ramanathan came to my rescue and said, “He is very intelligent. And does extremely useful work.” Dr Rajan affirmed this statement.

“This morning I too said his pamphlet was well written. Does it follow that we have to pay him more? Not possible in the Congress. If he wants to be paid more for his intelligence, he should have taken up some other job.”

The matter was closed. I cannot tell you how anger welled up in me. But as the days passed, my anger turned into devotion. I can say that his ruthless dismissal of my salary demand seeded that devotion.

Much later, when I went to the Gandhi ashram in Tiruchengodu, and saw Rajaji living with his children in a hut thatched with palm leaves, I realized that he was not someone who stopped with giving advice to others. He had made immense sacrifices in his own life.

Rajaji’s appearance, speech, and all that I learnt about his rectitude and his life of sacrifice, instilled bhakti in me.

I had the same devotion for Mahatma Gandhi as I had for Rajaji. Of course, Mahatma Gandhi’s greatness is immeasurable. However, he is a man from Gujarat who does not know Tamil. So, there is some difficulty in absorbing his teachings. But Rajaji belongs to our own Tamil realm. What he speaks in our mother tongue goes straight into our hearts.”