Gowri Ramnarayan

Translator of the biography Kalki Krishnamurthy: His Life and Times

In an Alfred Hitchcock film, you see Alfred Hitchcock, you don’t even remember the writer whose book made the film possible. Think of Godfather and you remember how Francis Ford Coppola and Marlon Brando turned pulp fiction into a classic film.

Many Indian films have been based on books – classics among them. But I have never seen the author’s name highlighted with respect and fanfare as with auteur Mani Ratnam’s PS1 has done. Not only does the film and its promos acknowledge Kalki as the author, but attribute the success of the film to Kalki’s genius. Mani Ratnam has indeed taken excruciating pains to present PS1 as the author’s vision. His concern from start to finish was ‘how can I present Kalki’s characters as the author imagined them’? And of course, Ponniyin Selvan became a film only because Mani Ratnam loved the book. A love that has been shared by 4 generations of readers.

Ponniyin Selvan, the book, has always been the bestseller in the history of Tamil fiction. But after the film’s release it has set new records in sales. There has also been a huge boost to every translation of Ponniyin Selvan. On YouTube and blogs, there are narrations of condensed versions of this historical saga – in time slots from 10 minutes to two hours. In Tamil, English and even Hindi.

Ponniyin Selvan, the book, has always been the bestseller in the history of Tamil fiction. But after the film’s release it has set new records in sales. There has also been a huge boost to every translation of Ponniyin Selvan. On YouTube and blogs, there are narrations of condensed versions of this historical saga – in time slots from 10 minutes to two hours. In Tamil, English and even Hindi.

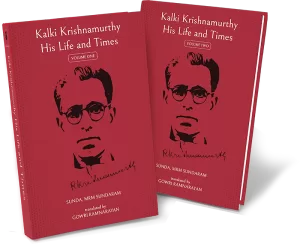

In addition, the film has stimulated interest in other books of Kalki as well. And in my English translation of the cult fictionist’s biography by ‘Sunda’ titled Kalki Krishnamurthy: His Life and Times. Why? Because, more and more people want to know about Kalki’s world. Because they realize that they will enjoy their favourite Kalki book far more by getting close to the author’s life, thoughts, dreams and actions, all of which really make his writing what it is.

Stories about Kalki by members of my family have always a part of my life. But I learnt far more from the way Kalki’s biography puts all those facts into context. I learnt about what went into a writer’s mind to stimulate his creative vision.

Ponniyin Selvan was the first book of Kalki that I knew, because as a child I was lucky to have my uncle, Kalki’s son Rajendran, read all the five volumes aloud to me. I was mesmerized by Vandiyatevan’s adventures. It is not Arjuna or Karna, but Arulmozhivarman who continues to be my all-time role model of the hero.

As I grew in years, I found other works of Kalki more interesting, more admirable. Alai Osai is far more satisfying as literature, and its vision of the Indian nation stuns me with its prophetic resonance.

Poonkuzhali’s Song from Kalki’s Ponniyin Selvan sung by Sriranjani Santhanagopalan

I also saw that Ponniyin Selvan’s sprawling and multi-stranded narrative has its glitches. It certainly leaves many threads hanging in mid air, There are unreconcilable contradictions, suggesting that midway through the writing, the author changed his mind about what he wanted a particular situation to signify. There are some nebulous factors about the characters, including sudden changes of mind without clearly developed reasons for their about turn. For example, can we ever understand why strong, independent, fearless Poonkuzhali, who loved Prince Arulmozhi so passionately, could suddenly agree to marry her cousin Sendan Amudan? But his readers were too spellbound by the surging narrative to notice these little blips.

Understandable, the blips I mean. Kalki wrote the novel to be serialised every week in his eponymous magazine. It was not his sole activity during that period. As the editor of his magazine he had to write the leader, other essays on current socio-political issues, critiques on the arts from music/dance to theatre/cinema, special articles for special occasions, commission other works, supervise the editing and so on. He was also raising funds for several causes, giving special lectures on a variety of subjects, enjoying literary soirees, attending literary events in Chennai and elsewhere, fund raising to build the Gandhi Mandapam in Madras, and supervising its construction with visits to the site.

He also had his first grandchild in 1950 (yes, that was me!), and became a doting grandfather, driving everyone crazy with his concern for the child, wanting to spend all the time he could with her.

My uncle told me that he wrote the Ponniyin Selvan chapters at night, after dinner, and after the child went to sleep, and would leave them on the table, to be sent to the press in the morning. He also never tires of repeating the story of how I, a completely spoilt brat, tore up an entire weekly instalment. And how Kalki just picked me up fondly and ordered my uncle to paste the scattered bits together and send them to the press!

Kalki wrote this 2500 page epic without preparing any premeditated plot structure or synopsis, or any notes about the plot or the narrative flow of the novel. All he had were reference materials. What were they?

Elango Kumaravel discusses PS 1

Sunda has listed the books he could authenticate as Kalki’s sources:

KA Nilakantha Sastri’s The Colas (English). Sadasiva Pandarathar’s The History of the Later Cholas (Tamil) Rajaraja Chola – A Balasundaram, The History of the Pallavas – Ma Rajamanickam Pillai, Pallavas of Kanchi – R Gopalan, The Pallavas – Prof Dubreil, Pallava Architecture – AH Longhurst, Administration and Social Life under the Pallavas – Dr C Meenakshi, The Sangam Age – TG Aravamuthan, Ancient India – Dr S Krishnaswami Iyengar.

Sunda adds:

Remember the old box of the astrologer in Ponniyin Selvan, where the horoscopes of several members of the royal families were stored? Books, and other historical information about the people to whom those horoscopes belonged, and notes about innumerable persons connected to those people, were stored in Kalki’s old trunk!

The profound concentration and utilitarian approach with which Kalki had read Sadasiva Pandarathar’s book on the later Cholas are obvious. Its pages filled with question marks, exclamation marks, underlined sentences, and margin notes in English and Tamil such as – “Useful information”, “Matter suitable for the novel”, “Mere guesswork”, “This is my inference”.

The 75th page of this book contains these words: “Princess Kundavai was given in marriage to Vallavaraiyan Vandiyatevan. He must have belonged to the dynasty of the southern Chalukyas living in the Vengi realm. “

Rejecting the second fact Kalki wrote in the margin, “Vallavaraiyan could have been a prince of the Vaanan tribe.” Confirming this fact later – the source and nature of this evidence remain unknown – he turns Vandiyatevan into the protagonist who strides through the novel from start to finish – as a gallant warrior, friend, and lover. Kalki has given him space and status equal to Arulmozhi Varman, whose name gives the novel its title. Shaping Vandiyatevan with great ardour, and with all his literary skills, Kalki ends his novel by wishing him, “May your name last forever!” And through that same novel, he makes his own wish come true.

When Kalki decided that this warrior belonged to the Vaanan clan, he recalled how (scholar-aesthete) TK Chidambaranatha Mudaliar (TKC) had sung a few venba verses about the great king who had founded the Vaanan dynasty. He wrote to TKC at once, requesting him to mail those and all other similar poems. Reading the verses (that arrived post haste, with many exclamations of “Bale! Bale!”, Kalki stored them carefully in the steel trunk, now his encyclopedia. As he wrote the novel, he used some of those verses in appropriate situations. Or he created situations to use them. Let us look at one such situation:

Vandiyatevan gets trapped in political intrigues as soon as he enters the Chola realm. He rushes to consult the astrologer in Kumbakonam, engages in some word play, and finally asks him to predict his future, saying,

“Be quick, it is getting late, I must hurry!”

“Where do you want to go in such a hurry?”

“Can’t you discover that in your charts?”

“My friend! There must be some foundation for making forecasts. A horoscope. Or the date and the reigning star at the time of birth. At least the name of the person and his native place.”

“My name is Vandiyatevan.”

“Ah! Of the Vaanan clan?’

“Yes.”

“Vallavaraiyan Vandiyatevan?”

“Indeed!”

“Tambi! Why didn’t you tell me right away? I think I have your horoscope.”

“I see! But why do you have it at all?”

“What else do you think astrologers do? We collect and store the horoscopes of boys and girls belonging to illustrious clans.”

“But I was not born in any illustrious clan!”

“What are you saying? So many great poets have sung about your Vaanan clan!”

“Why don’t you recite one of those verses?’

The astrologer recited a verse:

Vaanan pugazh uraiyaa vaayundo? Maagadarkon

Vaanan peyar ezhudaa maarbundo? Vaanan

Kodi thaangi nillaada kombundo? Undo

Adi thaangi nillaa a-ra-su?

“Is there any tongue that has not sung of Vaanan’s glory? Any chest on which Vaanan’s name is not tattooed? Any staff that does not carry Vaanan’s banner? Any realm which does not bear the glory of Vaanan’s rule?”

Sunda mentions other literary works that Kalki had read and found useful in writing his historical narratives: Pura Nanooru, Silappadikaram, Kalingathu Parani, Nandi Kalambakam, Periya Puranam, the poetry of the Saiva and Vaishnava canons.

Kalki did not write for scholars or for the elite. He never underestimated the lay reader. On the contrary, he scattered a range of verses, quoting from the ancient & the medieval, to times closer to us.

Just look at the zillion quotations in Ponniyin Selvan. In Volume One alone you have pasurams by Nammazhvaar and Periyaazhvar, Appar’s poem, Buddhist monks’ prayer for Sundara Chozha’s health and well being, a Sangam verse about the wealth of the ancient Chola capital Poompuhar. Kundavai’s friends dance to the Aaichiyar kuravai from the Silappadikaram. His descriptions of the old towns of Tiruvaiyaru and Pazhaiyaarai are taken from the poets Sambandar and Sekkizhaar. Not satisfied with this diversity, Kalki also writes his own song for the Krishna festival in Pazhaiyaarai!

Kalki surely thought that history would become real and vivid with cultural references. We saw that in the way he brought the Vaanan poem, attributed to Kamban, into the history he gleaned from Sadasiva Pandarathar’s book.

Kalki’s novels were enhanced by his familiarity with their visual settings. He travelled extensively through the regions where he located his novels. For Ponniyin Selvan, he travelled even more widely across Tamil Nadu and Sri Lanka. His accounts of those tours were collected and published as the travelogue Nam Tanthaiyar Seida Vindaigal, marvels wrought by our ancestors.

Young artist Maniam accompanied Kalki on those trips. His illustrations bring the joys of the visual along with the word. We must remember that in the 1950s, these pictures must have been indispensable for readers to visualize what the characters and the locations looked like. They were vital to the story. And indeed in its costume and ambience designs, PS 1 follows Maniam’s illustrations more than ancient sculptures, bronzes or murals.

Any number of people tell me about how their entire families waited for the weekly instalments of Kalki’s novels with bated breath. How they quarreled about who should read it first. And how the matter was sometimes settled by one person reading the chapters aloud for everyone. Some households bought two copies. Everyone read Ponniyin Selvan. A friend told me that his high court judge father and his social worker mother read it, so did their teenage children and their cook, while the car driver read it aloud to the gardener.

The national Audit Bureau of Circulation announced that Kalki the magazine, had the highest number of copies sold – among all the newspapers and magazines, in every language in India.

True. Today, as a writer, Kalki is best known for his historical fiction, a genre he introduced to Tamil for the first time. However, his trail blazing historical novels Sivakamiyin Sapatham, Parthiban Kanavu and Ponniyin Selvan are not pioneering efforts. They emerged as fine, finished works of literature, and role models for fiction writing cast in a brand new style.

Mani Ratnam – an exclusive interview about the making of PS 1

Why did he opt for this particular genre?

I think it is obvious that he used the swashbuckling genre of the historical novel to redefine the goals for the new India he dreamed of, a nation emerging from 150 years of colonial enslavement. Having devoured Walter Scott, Victor Hugo and many more modern historical fictionists, he became convinced that by presenting the magnificence of his own country through historical fiction, he could arouse his own people from the torpor and apathy engendered by colonial rule.

The best way of replacing their sense of insecurity and inferiority with pride and confidence was to remind them of the magnificence of their past heritage. That is why Parthiban Kanavu is all about a king dying to achieve freedom for the realm before his son fulfills it. Sivakamiyin Sapatham has much more to say about the values that the people of India had to nourish and cherish, to make themselves deserve independence. (It is possible to see shades of the idealistic Nehru with his ardour, love of the arts and more, in Mahendra Pallava, and the uncompromising integrity matched by valour in his son Mamalla Narasimha, qualities hebelieved to be integral to leadership in modern India).

Ponniyin Selvan was launched in 1950, the year India became a republic. It meant that that its leaders and citizens had to reclaim, repossess, strengthen and add to the nation’s progress, renaissance, re-formation.

As a political journalist, Kalki knew all the dangers lurking within and without. Corruption and conspiracy, malice and one-upmanship, hypocrisy and deceit, evil and violence, in all their many forms. He had seen power madness upclose.

As a writer, his responsibility was to urge the citizens of the newly emerging nation, that we had to choose as our leaders, persons of unimpeachable virtue, who were also wise, sagacious, selfless, fearless, valiant, compassionate, persons who would uphold noble values, follow dharma. The best leader was one who did not crave power, but wanted to serve selflessly.

It is said that since the Mahabharata was shaped in its rounded form during Asoka’s era, the character of Yudhishthira, known as Dharmaputra, was shaped by the bards to resemble the Mauryan king in his noblest attributes. Similarly, Kalki, who had lived when Gandhi walked the earth, shapes Arulmozhi with all the values he revered in the Mahatma.

Prince Arulmozhi, who would later become the future Emperor Rajaraja I, and establish an empire as vast as that of the Mauryan Asoka, is imbued with physical prowess matching his moral strength. He is humble, compassionate, intelligent, loyal and true. And most important of all, he has no interest in power.

During his battle in Sri Lanka, he ensures that the civilian population is fully protected. He insists that food for his troops must be sent from the homeland, because he would not deprive the people of Sri Lanka of their food or subject them to hardships. He has no quarrel with them, only with their king who has been interfering in the internal politics of his motherland, the Chola kingdom. Just as Socrates refused to disobey the order of the state which decreed that he should die by drinking poison, Arulmozhi refuses to disobey the order of the king, his father, even when the king unjustly commands that the prince should be arrested and brought home from Lanka as a prisoner.

Arulmozhi varman respects everyone – a fisherwoman receives the same courtesy that he accords to a highborn prince. He has respect for every creed in his realm. He will never leave a dependent stranded, never forsake a friend. He can renounce a kingdom because he thinks someone else has a greater right to the throne.

Without sloganeering, Kalki embedded his inmost convictions in Ponniyin Selvan. I will cite two examples. Writing about a society driven by class distinctions, he underscores the fallacy of grading human beings on the basis of their caste or class. In a patriarchal society, he exalts intelligence and savviness in women.

I think these values are of the utmost importance to us today, in our times of division and strife, caste politics and hatred of other creeds.

Hundreds of letters rained on Kalki when the concluded the novel. Many blamed him, because they thought he had finished the story abruptly. They wanted more. They were not willing to let go of the characters who had become a part of their lives. Many asked him to continue.

But Kalki would not. In his epilogue to Ponniyin Selvan Kalki explicitly declares that the climax of the story is Arulmozhivarman’s sacrifice, and that every incident in the story had progressed toward that monumental event. If readers failed to grasp this, the author would have to humbly accept blame.

He would accept blame, not for his skills as a storyteller, but for not having made his readers understand clearly that he had underscored the magnificence of their heritage and set up role models for guidance, to underline the hazards on their trail, even as he spotlighted India’s hopes for a brilliant future. Through the novel he had urged the people of his land to make themselves fit and ready for a better world, and to create that better world.

Karthik Sivakumar, the actor better known as Karthi, speaks about Kalki Krishnamurthy and PS1

I will conclude with this. Recently I said to a friend, “I can’t understand this obsession with Ponniyin Selvan. I think Sivakamiyin Sapatham, and certainly Alai Osai, are more brilliant!”

He laughed and replied, “But they are great novels. Ponniyin Selvan is a great story!”

And because it does not state, but implies truth, what can impact on human lives more than a story?

Thank you!